Wedoany.com Report-Nov 23,A new study examines the effects of wind turbines on our visual landscape.

Most Americans—between 70% and 90%—are in favor of harnessing wind power.

That is according to one study looking at decades of public acceptance of wind energy nationally. But wind power projects can sometimes be stifled by local opposition, in part because of how people tend to view the way turbines look. Little about that opposition has changed in the last 50 years.

“Visual concerns are among the top reasons people are opposed to wind projects,” said Mike Gleason, a geospatial data scientist at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) who led a first-of-its-kind study examining the visual impacts wind power has at the national scale.

The research, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Wind Energy Technologies Office (WETO), provides a new lens through which planners, policymakers, and researchers can view the current fleet of roughly 70,000 turbines across the contiguous United States.

“We’re thinking a lot about what a future with more wind energy could mean for communities and the landscape,” said Anthony Lopez, a senior energy researcher at NREL. “We are trying to look at the different aspects of wind deployment and contextualize those in a manner that means something to people.”

A Broader View of the Impact of Wind Energy Development

Currently, about 10% of all electricity in the United States—over 150 gigawatts of power—is generated by land-based wind. But while the fleet of wind turbines is large and growing, the visual impacts of it are proportionally small in terms of land area, population, and sensitive visual resources.

“We’re examining the overall impact that wind turbines have on the landscape, specifically the scale of visual change they introduce,” Gleason said. “This study aims to provide a broad context for these discussions, offering an objective perspective to better inform some of the narratives that may exist.”

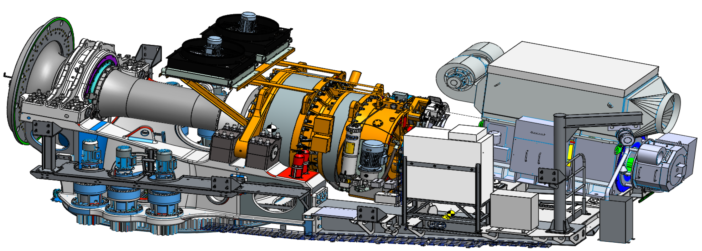

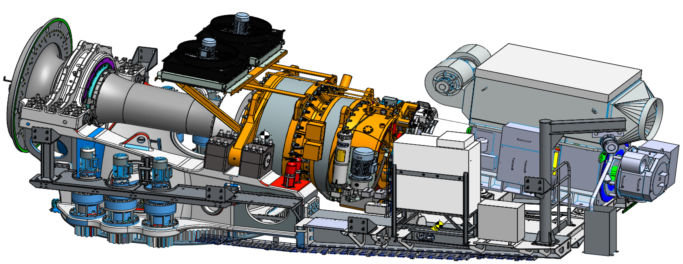

The team took a unique approach in their study, combining methods from two prior, smaller-scale visual impact assessment studies and applying them to a comprehensive geographic information systems (GIS) dataset of nearly 70,000 land-based wind turbines in the contiguous United States. Ultimately, that data helped create a high-resolution map of the total visual magnitude of the current U.S. turbine fleet.

To do that, NREL’s team divided its examination of the turbine fleet into three main steps:

First, they modeled the total visual magnitude—the proportional amount of space something may take up in someone’s field of vision—of impacts from installed wind turbines using 3D simulations and GIS tools.

Second, they took those methods and applied them to the existing land-based turbine fleet of the contiguous United States.

And third, they examined how visual impacts of turbines are geographically distributed relative to key environmental and human factors.

“What we found is that turbines are technically visible for only 12% of the population, which is proportional to the contribution of wind energy to the grid,” said NREL geospatial data scientist Marie Rivers. “But most of those impacts are minimal or low, and I think that’s a positive story for wind energy development because it suggests that to some degree that while more turbines may be installed on more land, the population and scenic resources may not be impacted by them as much.”

Seeing the Results

The overwhelming majority of the land in the contiguous United States—about 93%—fell into the three lowest categories where visual impact is concerned. And that number is even higher relative to population: more than 97% of the population either saw low, minimal, or no visual impact. “The results suggest that people’s perceptions of the visual impacts may be exaggerated relative to how we were able to quantify them,” Gleason said.

Through this study, the team was able to draw several key conclusions:

A small percentage of land area, people, and sensitive visual resources are impacted by wind energy development in the contiguous United States despite turbines being visible in many places across the country.

The highest visual impact from existing turbines is geographically concentrated in deserts and plains.

Although increased density of wind development consistently leads to visual impacts across a greater proportion of land, it does not always lead to impacts to a greater share of the population.

Creating a Vision for Future Wind Energy Studies

The study both clears the air on a number of perceptions surrounding wind energy development in the contiguous United States and opens the door to further studies. Gleason and the team analyzed wind turbines at a national scale, meaning they were not looking to determine what causes different perceptions of the visual impacts of wind energy.

“This research really helps inform some of the social sciences and gets them off and running quicker to understand the impacts to local communities,” Lopez said. “I also hope that this type of work helps further the discussions around what an energy future with wind as a main electricity generator could mean for people.”

Some of the questions the study could help researchers examine next include subjects like the evolution of wind turbines: What could happen as they get taller but may be spaced further apart? How could that potentially change the patterns in visual impact?

The study also gives future researchers a platform to dive deeper into why certain regions around the country may have had higher or lower visual impacts than expected.

“As we model future decarbonization scenarios, this study gives us more tools in our tool bag to explain what changes to the landscape could look like and how they compare to the current landscape,” Gleason said.

To that end, the team has released the software developed and used in the study under an open-source license, meaning it is publicly available for other entities to use for further research or commercial applications.